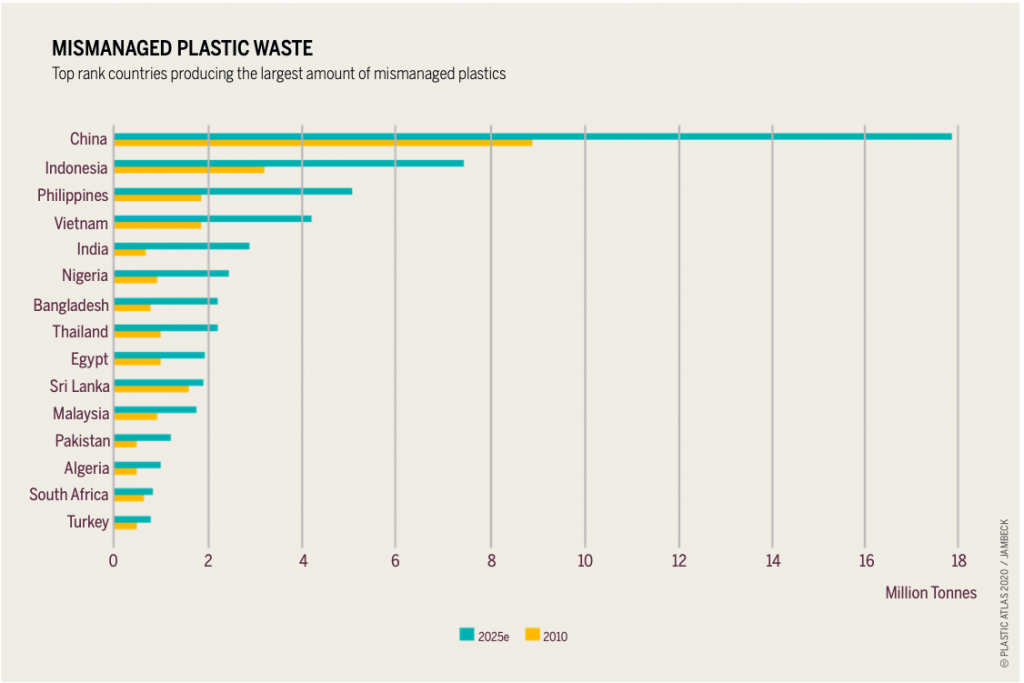

Nigeria is building up on plastic waste and is now the world’s sixth largest producers of mismanaged plastic waste.

Our world in data, defines mismanaged waste as material which is at high risk of entering the ocean through wind or tidal transport. It is also the sum of material (plastics) which is either littered or inadequately disposed.

Across high-income countries such as those in Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea who though generate a lot of plastic waste compared to Nigeria, incidences of mismanaged plastic wastes are minimal due to the effective waste management infrastructure and systems they have developed. This in other words means that their discarded plastic waste (even that which is not recycled or incinerated) is stored in secure, closed landfills.

But the situation is not the same for Nigeria as disclosed by a new report – Plastic Atlas: facts and figures about the world of synthetic polymers, published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Nigeria.

“By international comparison, Nigeria ranks among the top ten countries producing the largest amount of mismanaged plastic waste,” the new report revealed.

Just like the fictional Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland said: ‘If you don’t know where you are going, any road can take you there’; a good number of Nigeria’s about 200 million people perhaps don’t know they’re living in communities floating in plastic wastes. This by key environmental standards is a hazardous road to be on.

Clearly, after China which now has the potential to raise the volume of its mismanaged plastic waste to about 18 million tons per annum in four years – 2025, as well as Indonesia – almost 8 million tons, Philippines – 5.5 million tons, Vietnam – 4.2 million tons and India – 2.5 million tons; Nigeria is equally about to more than double her yearly plastic waste production to 2.3 million tons in 2025.

This then means that Lagos which accounts for most of Nigeria’s plastic wastes, and some of the country’s coastal towns and cities will have more plastics littered and messing up our environment.

A rough ride for Nigeria

Littered plastics as disclosed by Heinrich Böll’s report is a threat to Nigeria’s environment and solutions to address the threats appear farfetched.

Published in partnership with Break Free From Plastic to give palpable insights on the particular challenges of plastic wastes in Nigeria, the report pressed on the need for urgency in managing plastic waste appropriately.

“With plastic production and consumption set to increase, the country urgently needs to invest into its waste management capabilities and regulatory environment to tackle the mounting effects of plastic pollution on people and the environment,” it said.

According to it, the country lack effective policy frameworks to address the plastic threats, and this has remained a major challenge in managing the resultant crisis.

“Such gap would have to be filled to halt the current damages caused by plastic pollution in Nigeria,” it added.

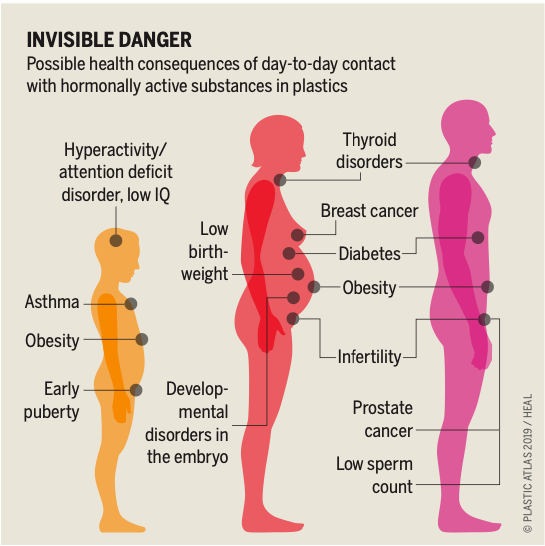

“Many of the chemicals in plastic have an effect on human health. The consequences may be both serious and long-term.”

Reliable statistics on the volume of plastic waste produced in Nigeria are difficult to obtain but figures from the Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA) estimate that Nigeria generates up to 35 million tonnes of municipal solid waste annually, the report explained.

Out of this, 10 to 15 per cent is composed of plastics, pointing to a growing environmental problem and the challenging task for government to find effective solutions.

Further, Nigeria’s average plastic waste generation is hard to measure but estimates put it between a low of 7.5kg per capita per year to 45kg per capita per year for cities like Lagos.

Despite the poor data set, plastic consumption is rising in Nigeria where over 850,000 tonnes of plastic wastes are reportedly mismanaged every year.

The country is also Africa’s second-largest importer of plastics in primary form – after Egypt, which is used for making supermarket bags, plastic bottles and furniture, amongst others.

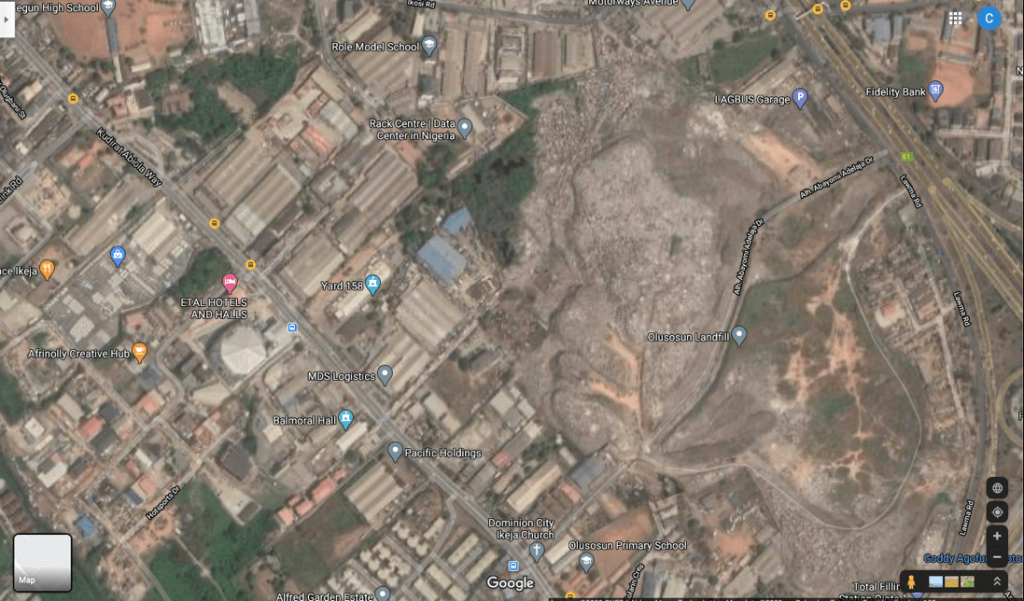

Disposal methods often used for these plastics include dumping on landfill sites and open burning as seen in the 100-acre Olusosun landfill and Gosa landfill Lagos and Abuja respectively; this results in hazardous soil and air pollution as some categories of plastics contain plasticizers and flame retardants.

Lagos’ 100-acre Olusosun landfill houses thousands of scavengers.

Regulations, rare compliance

Nigeria, reportedly notorious for enacting loads of laws that never really get implemented in the long run actually passed a law in 1988 to safeguard the environment. It established the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) Act; and this made Nigeria the first African country to set up a national institutional framework for environmental protection.

According to Heinrich Böll’s report, though there were regulations that included the plastic material and synthetic industry, these were focused on only limiting their effluents, emissions and discharge of hazardous substances.

The FEPA, it explained was unable to enforce its own regulations and was merged with other relevant ministries to form the federal ministry of environment in 1999.

In 2007, the government repealed the FEPA Act and created the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) to effectively manage the country’s enforcement of environmental laws and regulations; NESREA remains under the environment ministry and its Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR) programme remains the closest working government policy tackling plastic waste in Nigeria.

Accordingly, the EPR programme originated from Sweden in the 1990s as a policy strategy to encourage environmentally responsible product manufacturing and disposal; NESREA first published its EPR operational guidelines in 2014 and commenced operation in 2016 starting the food and beverage industry which probably produces the largest amount of plastic waste in the country.

In context, the EPR seeks to provide a framework for collaborative partnerships between government and the private sector towards achieving zero waste; it sought to make manufacturers or brand owners responsible for the entire lifecycle of their product, particularly their take-back, recycling and final disposal.

Its process is collectively managed through third party organisations called the Producers Responsibility Organizations (PROs), such as the Food and Beverage Recycling Alliance (FBRA), but the report noted that only 10 companies are currently registered under the FBRA.

“Many manufacturers responsible for plastic waste generation have been slow to sign-up to the alliance,” it explained, adding that, “there is the problem of a lack of understanding of how the policy is to be implemented due to inadequate information and poor communication between government and the industry.”

Similarly, the definition and classification of the stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities according to the report remain unclear, while the economic costs and incentives of the programme remained undetermined.

“Most significantly, insufficient funds for monitoring and enforcement have weakened the process. Nonetheless, the PROs continue to work with small community-based vendors through partnerships to carry out engagement and advocacy, collection and recycling activities,” the report added.

Further, another attempt was made to regulate Nigeria’s mounting problem of plastic waste in 2018, when a member of the House of Representatives introduced the Plastic Bags (Prohibition) Bill.

The bill sought to prohibit the use, manufacture and importation of all single-use plastic bags used for commercial and household packaging; and prescribed heavy penalties for offenders, including of imprisonment. It however did not get signed into law even though the House of Representatives passed it in 2019.

“In all, despite some efforts by lawmakers and the Nigerian government, the necessary reforms are beleaguered with a lack of political will to follow through and confront the plastics crisis,” said the Heinrich Böll’s report in a clear illustration of a looming environmental crisis.

Plastics, as explained by environmental scientists harm the environment; and there are indeed thousands of landfills in Nigeria, buried beneath each one of them are toxic chemicals from plastics which eventually drain out and seep into groundwater, they also flow flowing into Nigeria’s lakes and rivers, thereby corrupting aquatic life.

Additionally, poisonous chemicals have been proved to leak out of plastic and are found in the blood and tissue of many people. When people are exposed the poisonous chemicals, it could result to cancers, birth defects, impaired immunity, and endocrine disruption amongst others.