Stakeholders are excited about the mini grid regulation recently approved and signed by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC), which is good. But can it jumpstart the country’s DRE market?

Recently, the Nigeria Energy Regulatory Commission (NERC) matched its previously declared intentions of jumpstarting Nigeria’s plan to generate and distribute more electricity chiefly from renewable energy sources with its approval of a mini grid regulation in the sector.

By signing in the regulation, NERC effectively chose to relieve large companies already in the business, of the task of providing energy on a small scale to small users who have sadly gone for years without electricity supplies.

NERC’s action was according to reports, in line with the federal government’s several pronouncements to improve electricity supplies to Nigerians across board, and its implications are quite enormous considering Nigeria’s current plight.

Nevertheless, the regulation defines a mini-grid as “any electricity supply system with its own power generation capacity, supplying electricity to more than one customer and which can operate in isolation from or be connected to a distribution licensee’s network.”

Within it, the term ‘mini-grid’ is used for any isolated or interconnected mini-grid generating between 0 kilowatt (KW) and l megawatt (MW) of generation capacity. This basically means that a mini-grid combines the functions of distribution and generating companies altogether (Discos and Gencos) making it a legal entity concerned with generating and distributing power within a specified small area or community.

Further, the regulation delineates mini-grids into two broad categories namely: isolated and interconnected mini-grids. For isolated mini-grids, as the name implies, they are mini-grids which services communities that have no structural connection to whatever Disco it falls into. Whilst the interconnected mini-grids are those which make agreements with existing Discos to serve underserved communities in their networks, meaning areas which are connected to the transmission grid but have insufficient electricity to show for that connection.

What does this mean for power generation in Nigeria and the distributed renewable energy market? Simple. It should by all standards provide electricity to unserved or underserved population of the country.

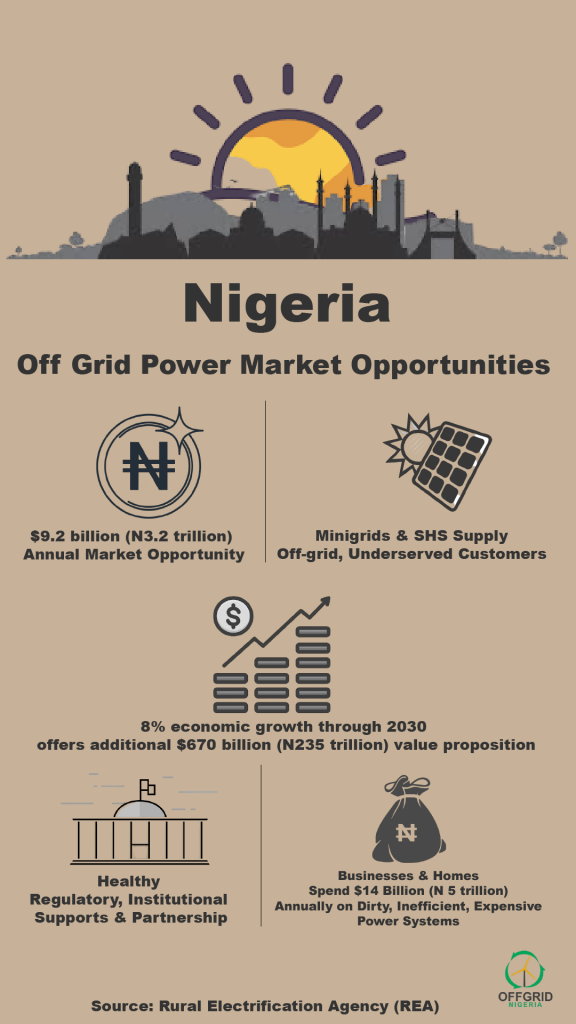

The International Renewable Energy Association (IRENA), had repeatedly stated that about 90 million Nigerians remain unconnected to the national transmission grid today, and a host of others connected do not have stable power. This regulation would try to change this worrisome situation by ostensibly permitting any organization or investor to become an electricity supplier within any given area.

Now, the interesting part of it is that a community may choose to even incorporate itself as a legal entity and float a mini-grid even if that is solely for its consumption, as long as it follows the outlined guidelines for that process.

Even for pastoral communities which usually have no connection to the grid, the option of isolated mini-grids could provide them a big reprieve, giving them the much needed exclusive coverage and focus that will invariably arise from having a single client base.

According to the NERC, the outlined steps for a company to get licensed by it to become a mini-grid developer varies depending on both the choice of mini-grid options the developer intends to take, as well as the projected output from the grid.

However, the universal requirements demand an application to the NERC on the particular area a developer has scouted; written consent from the Disco where that area falls into; an agreement with a body constituting at least 60% of the community which would be billed under the mini-grid as a representative of the entire community and validating that all equipment, assets and lands necessary for the mini-grid have been either leased, bought or granted for the project.

Observed by industry stakeholders as a good step, the regulation is said to have the potential to bring a wave of positive changes to Nigeria’s power sector, especially the DRE subsector, but we are of the view that it is currently heavily tied to the Discos, which may not turn out to be in the best interest of the country considering her troubles with operators of the Discos since the sale of the assets to them in the power privatisation exercise.

Also, the question of whether capping the output for mini-grids to 1MW was wisely thought out when considering Nigeria’s deficient powers capacity could be tenable. Obviously, any policy or projects in Nigeria’s energy need to impact both residential and commercial users, as such, some commercial industrial scale users would choose to generate power for themselves if given the option as the regulation has, but as it is, 1MW may prove too little for some industrial scale operations to consider investing in.